Asiyah Robinson and Klasom Satlt’xw Losah centre friendship,

purpose, and hope for these times —and beyond.

#242ToTheWorld

It’s an early September evening in 2019, and Asiyah Robinson is moving lightly and purposefully through a crowd of friends and supporters. In the wake of Hurricane Dorian, the Bahamas Relief Fundraiser, held at Klub Kwench in Victoria, BC, Canada is not simply another of the countless community events that Asiyah organizes or participates in—Dorian, as Asiyah later states, was the most devastating hurricane in the history of her country. On the night of this fundraiser, Asiyah has only just learned that her missing father has been found and is now safe, though the damage to her island homeland is catastrophic. With a mixture of relief and grief, Asiyah smiles, hugs those around her, and presses her hands into others’ hands in gratitude.

Hurricane Dorian hurt so many. It took lives. Destroyed homes. Broke spirits.

Fast forward to a year later—2020, which seems oddly unframed by a January-to-December parenthesis. 2020 is indeed something concrete and ethereal all at once. Much like Asiyah. The twenty-four-year-old possesses a heightened self-awareness and an emotional maturity that belies her age. These qualities are coupled with a relentless optimism and a super-charged energy that seems barely contained in her petite frame.

Born and raised in Freeport, Bahamas, Asiyah made her way from her home island of Grand Bahama to Vancouver Island in 2014 to undertake post-secondary studies in biochemistry and chemistry at the University of Victoria. Last month, on the first anniversary of Hurricane Dorian, Asiyah remembered there were some hours when she genuinely thought her father had passed away. She shares how terrifying that was for her and how the anniversary brought those emotions rushing back. Feeling the weight of separation from her Bahamian family in these COVID-19 times, Asiyah longs for physical reconnection with them. She shares what she knows and what she misses: I know you are okay, my heart whispers, but I haven’t touched you or felt you.

I know you are okay, my heart whispers, but I haven’t touched you or felt you.

COVID-19, however, has not prevented Asiyah from connecting meaningfully with her vast Victoria family, nor has it slowed her volunteerism and activism in the wider community. One might even argue that the so-called Great Pause has further galvanized Asiyah as she transmutes loss and uncertainty into focus, compassion, and action. This type of community engagement comes naturally to Asiyah, as does gathering people around her. Recently, a mentor-friend of Asiyah’s, activist and educator Klasom Satlt’xw Losah (known to some as Rose Henry) of Tla’amin Nation referred to Asiyah as her daughter in a Facebook post—much to the surprise of Asiyah’s mother, Alisa. Asiyah is quick to put it in context: “I build relationships very fast, very easily. I can now say I definitely have an energy that feeds others, and I’m bubbly. Honestly, since I was a kid, people have been claiming me as their daughter. Listen, my mom is my best friend. My best friend. I have many people in my life who are very much like mother figures. My mom wasn’t upset, but she was very funny, asking: ‘Who is this woman claiming to be your mother?’”

Who is this woman claiming to be your mother?

When asked about Asiyah, Klasom Satlt’xw Losah— fondly and respectfully called Grandma Rose or simply Rose by many—leads with “Asiyah? Asiyah is awesome.” She then humorously references Asiyah’s trademark energy, wondering out loud what she’d be like “on caffeine.” Rose also acknowledges that it was precisely this energy that made her want to get to know Asiyah better. Rose can’t recall exactly where or how they, the young Muslim student and the Elder, first met, but she is certain it would have been in a space that championed social justice. Rose shares that as she got to know Asiyah “during walks at different events like Black Lives Matter, or when [they] were feeding the people of the streets, her energy just kept escalating.” Rose wishes she could have “just one ounce of her energy.” But there is a more poignant connection for Rose, a stronger thread that pulls her to Asiyah: “She is living the life that I had been denied. Through the foster care system and through the Sixties Scoop, I was never allowed to express the joy of being who I am.”

She is living the life that I had been denied. Through the foster care system and through the Sixties Scoop, I was never allowed to express the joy of being who I am.

The Sixties Scoop—a misnomer, as apprehensions continued well into the 1980s and arguably continue to this day— oversaw, through provincial policies, the apprehension of an estimated 20,000 Indigenous children from their homes to be placed in the Canadian child welfare system. Most of these babies and children were ultimately adopted into mainly non-Indigenous families without the consent of the parents or band. Rose, like other survivors, suffered the irreparable separation from and loss of family, a painful legacy further compounded by the tearing apart of the cultural and linguistic fabric of her own Indigenous identity.

“The transferring of our energy, passing on the torch to the next generation . . .”

These two women are transferring energy to each other in an ongoing mutual exchange of love, respect, and teachings. Mother, daughter, sister, friend.

“In our culture,” says Rose, “when we decide you are our family, we give you a position—you’re my niece, my daughter, my granddaughter; you’re my family now.” Rose may sometimes doubt her deep well of traditional knowledge, but for those who have spent any time with her, it is immediately apparent that every encounter and conversation is seized as an opportunity for knowledge transfer through storytelling steeped in Indigenous mythologies, natural histories, and lived experience. Rose is clearly making up for lost time.

As for Asiyah’s mother, Asiyah admits that, beyond the playful jabs on Facebook, her mom “treasures very deeply and truly honours” Rose and the other mother and father figures in her daughter’s Canadian life. The hard work of activism and community-building exacts a toll, and Asiyah has begun to recognize that her self-care regimen is lacking. “The ways I currently find value are through other people, through helping others, and not so much in myself, which is why it is very easy for me to go days without eating or drinking water or exercising or doing anything that feeds anything other than the work or the emails or the assignments. That’s my contribution. That’s the way that I give. And I sometimes don’t see my value outside of that.”

…it is very easy for me to go days without eating or drinking water or exercising or doing anything that feeds anything other than the work or the emails or the assignments.

Who is Asiyah?

When asked this question, Asiyah responds with laughter. “Oh, gosh. Who is Asiyah? The one thing I don’t want to talk about. Thank you for the offer, though. Great question. When I figure it out, I will let the rest of you know.”

“I am really trying to figure out who I am,” says Asiyah, “and recent events have made that a process that seems to need to happen faster because I need to be in a position to take a leadership role. Not to know who I am, but to know certain parts of me and believe that of myself. When it comes to me, the biggest part isn’t knowing who I am but believing I am who I think I am or I am who other people think I am. In my work, I’m either surrounded by youth who are interested in what I am doing and want to get more involved, or adults who want to know what’s going on in my head. And everyone in between. That terrifies me because I don’t know where I am sometimes. I also sometimes don’t even think that my voice needs to be heard at a particular moment, and yet people are asking for it. And so, for me, a big part of this journey is trying to figure out who I am, and what my value is to the things that are happening right now. And how I can prove, well, not prove that to myself, but let myself remember that I am worthy of being heard and that my ideas are worth it.”

And how I can let myself remember that I am worthy of being heard and that my ideas are worth it.

By “recent events” and “right now,” Asiyah is referring to the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement that rose up and out of many shocking and incendiary racist crimes, not least being the killing of George Floyd by police officers in Minneapolis, Minnesota on May 25, 2020. The global reaction to Floyd’s murder was overwhelming and complicated. Parsing the multiple, nuanced layers of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement is arguably unique to a geographic region, a city, a family, even an individual. For Asiyah, it became personal in a way she hadn’t anticipated.

“The Bahamas is a predominantly Black country—Black and Christian,” Asiyah says. She goes on to explain that she saw “Black people and Black excellence” everywhere in the Bahamas, and so it wasn’t an identity she “thought [she] had to think on, or really construct or deconstruct because [she] was just Black; it was what it was.” For these reasons, she had “always identified being more Muslim” than Black.

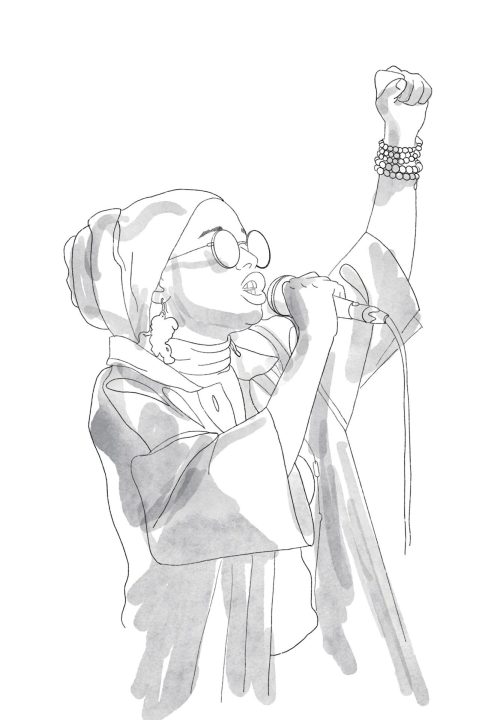

And yet Asiyah became one of the trio of core organizers for Victoria BC, Canada’s massive Black Lives Matter peace rally on June 7, 2020. When asked what the rally meant to her, she responds, “It was the first time that I ever consciously acknowledged and accepted my Black identity.” The statement is profound enough that an extended silence follows its utterance. Until, however, a rush of other thoughts bursts forward: “The rally forced me to hold myself accountable to the awareness that I had awakened in myself. What the rally has also done for me is send me into many spirals and brought more questions, millions of questions. For about a month now, I’ve asked: Have I been called to witness? Have I been awakened to witness? Have I been awakened to the level that I think I am to simply perceive and understand what is happening around me, but not actually have the vision, the power, the impact to be able to change any of it? It’s been very terrifying for me to unpack.”

Have I been called to witness? Have I been awakened to witness?

This new acceptance of her Black identity is also creating space for Asiyah to explore her intersectionality as a Black person, a Black woman, and a Muslim Black woman. She admits that intersectionality is not something she commonly sees embodied; she feels she is writing her own “how-to manual and figuring out [her] own steps because [she doesn’t] know who else to follow.”

Black and Indigenous Lives Matter

What may separate the BLM movement of the United States, and perhaps even global BLM protests, from the Canadian BLM movement is the visible and meaningful solidarity between Black and Indigenous activists and communities. Asiyah says that the June 7, 2020 rally cemented key relationships for her, from both “Black and Indigenous sides,” people she calls her “Black brothers and sisters and Indigenous cousins.”

It might seem obvious that systemic racism, discrimination, and racial inequity affect not only Black individuals and communities, but also other so-called racialized communities, including First Nations. However, many newcomers to Canada—and even those Canadian-born—have little knowledge of Canada’s dark history as it relates to Indigenous peoples, nor any understanding of Indigenous histories, languages, or cultural practices. For Asiyah, that awakening did not come until her second year of university.

Participating in an Indigenous Acumen Training program at the University of Victoria, she learned for the first time about the horrors of residential and day schools and the Sixties Scoop. Asiyah calls the learning experience “heartbreaking and gutwrenching,” but mostly she was shocked and frustrated, asking herself, Why doesn’t everyone know, and why didn’t I know when I first came to Canada? Asiyah acknowledges that the last residential school was closed in 1996, and says sadly, “I was born in 1996. That is a fact I quite literally will never forget.”

Why doesn’t everyone know, and why didn’t I know when I first came to Canada?

Naturally, Asiyah’s relationship with Rose is also helping her deepen her knowledge and connections to Indigenous culture. In some ways, Rose sees these strengthened ties across cultures, including across First Nations, as a new dawn—what she calls “the cultivation of hope.” Rose believes all oppressed groups are now uniting and crossing “colour barriers” because they are “seeing with the tth’ele’, the heart.”

Give my heart

“It is actually Islam that took me to Indigenous culture and understanding,” reveals Asiyah. She reflects on “walking with intention on the land” and on what Islam says about being on the earth, protecting the earth, protecting the animals and the plants, and the trees and water. She shares that “in the Quran, the Prophet Mohammed (peace and blessings be upon him) has been known to say in a Hadith that the earth is like our mother because, in Islam, we believe we were all raised from the earth and to the earth we shall return, and that water is sacred, as it is the source of life for all.”

This is not the first time Asiyah has recognized the link between her faith and Indigenous culture and practices. She once took a beading workshop at an Indigeneous Art Symposium at the Royal BC Museum called Making as Medicine. Asiyah found something “so mindful, grounding, and beautiful about creating something from such small little pieces.” She adds that “it was medicine” for her in a way she didn’t even fully understand. She was also smudged that day and was awestruck by the similarities of an Indigenous smudging ceremony to the cleansing practices of making duʿāʾ in Islamic ritual; she sees it as a mirror of her own faith practices.

This mirroring, or perhaps the seeing and feeling oneself in others—one form of empathy—can be a double-edged sword. In the context of anti-Black racism and violence, Asiyah shares that “for any Black person, when someone is murdered, it hurts on a deeply personal level. You recognize that person, you recognize that person in your cousins, you recognize that person in your friends, you recognize that person in yourself, and you recognize that person as a person. So, just on a simple human level, it hurts.” However, the sheer magnitude of historic and present-day systemic anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism and violence, combined with the relentless and graphic reporting and sharing by news outlets and social media channels, inevitably and unfortunately can lead to desensitization. Even this is a burden, Asiyah says. “I do sometimes feel guilty that when something happens I don’t feel as sad as the last time I heard it, or the first time I heard about a murder, or a killing, or a death. I feel guilty, like, Why does this life matter less? And it’s not like it does matter less, it’s simply that I’m trying to protect my emotions and not give my heart every single time something happens.”

…it’s simply that I’m trying to protect my emotions and not give my heart every single time something happens.

We are all connected

“In [Japanese] anime,” says Asiyah, “people are connected by a red thread, like a thread of faith or something. You’re connected to this person, who is connected to this person, who is connected to this person.” This analogy illustrates her growing awareness of the profound connections she has made.

“For those of us who are Indigenous and are very visual,” Rose describes this same notion as parallel train tracks. “The train tracks will never show how our lives connect until we reach the next town, the next intersection of hope, social justice, our past generations, and our strength.”

“Core to Black peoples,” says Asiyah, “is the fact that all of us bring our dialects, our food, our culture, our being and our mindset, and our colour in and of itself—the different spectrum of who we are. We really all need to genuinely talk about lateral leadership; we need to define what that looks like, what that means, and how we can raise each other up. There are so many intersections that make up me; there are so many intersections that make up you. We need to recognize that we can’t attack things in silos.”

Klasom Satlt’xw Losah, Grandma Rose, calls for all of us to “join forces together so there is no more violence, and no more missing and murdered Indigenous people. If we’re going to change, we need to feed the people nutritious food and positive thoughts, and offer emotional, spiritual, and mental supports.”

If we’re going to change, we need to feed the people nutritious food and positive thoughts, and offer emotional, spiritual, and mental supports.

Together, over this past difficult year, these two collaborators have demonstrated commitment, patience, and curiosity—all of which are vital to building meaningful relationships that transcend differences of every kind, and that recognize and honour the complexities of every being. We stand at this intersection of hope together, and the example of Rose and Asiyah’s friendship and work offers a promising blueprint for a re-imagined future that is still ours to co-create.

Rose’s Cedar Hats

“The cedar hat, for us Indigenous people of the Coast Salish, or anywhere on our territories, symbolizes the medicine of the cedar tree. Cedar is our medicine. The cedar itself comes from culturally moderated trees (CMT). Only specific trees from the cedar family are stripped of their bark, and that bark is what we use to make hats, braided bands—anything to do with cedar comes from the trees that have been picked by the Elders, and only picked a certain time of the year. And never, ever have we stripped a tree to the point that it will die. It’s supposed to be a great honour for people to receive cedar hats and eagle feathers and different traditional things. So, the cedar hat is for the Elder who is willing to share their wisdom. I didn’t know I was doing it, but I guess I am! I have been given three cedar hats. The first cedar hat that I was given was by the medicine man from Nitinat. I refused to take it the first three or four times even when he kept saying it’s yours, it’s yours. He said he had a dream that the hat was supposed to come to me, but I also understood that when people start giving away their precious items, that means they are getting ready to go on the journey to the spirit world. So I refused. I didn’t want to lose him. I didn’t want that to happen, so I refused and refused and refused. He finally said, take the hat, so I did. I think the hat must be seventy or eighty years old, maybe even older.

I was given another hat from my home territory because of my willingness to share my experience about growing up in the foster care system and how I not only identify the negatives, but I am also prepared to deliver the solution. The third hat was given to me by a very well-known artist. He said, you are seeing the world very colourfully, very bright, like it’s alive—in the middle of a pandemic! I told him: because it is alive! If we go down into the darkness all the time, we are going to kill ourselves. The Creator has no intention for this to happen now. We’re supposed to learn our lessons from this pandemic.”

—Klasom Satlt’xw Losah

This article was originally published in print in January 2021.

Read all the #WeAreHere featured articles here