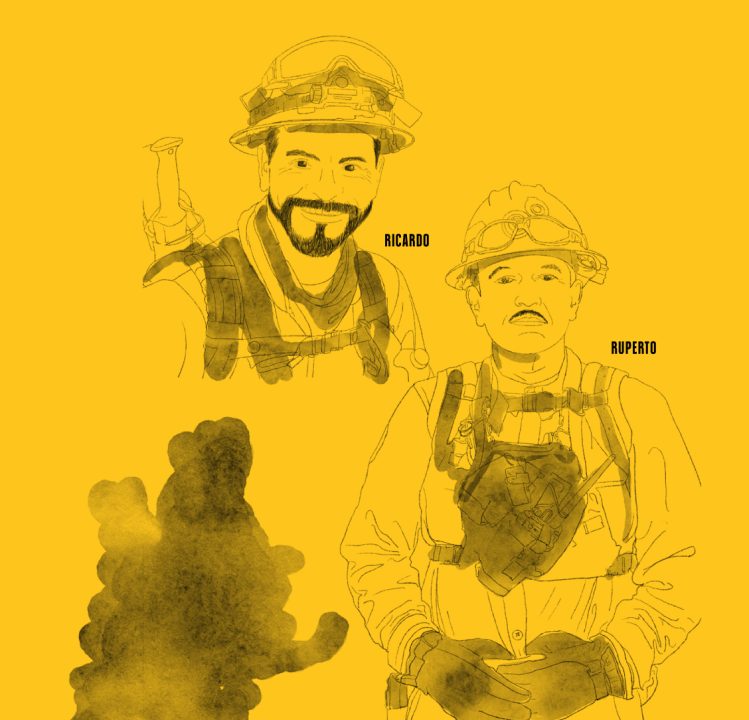

Illustrations by Salchipulpo

Climate change is amplifying worldwide weather events to the extreme. Here in British Columbia, this reality not only extends our ‘typical’ wildfire season, but also the size and frequency of the blazes, making the situation on the ground increasingly unpredictable in recent years. What has become predictable over the past decade, however, is the critical need for international resource-sharing during wildfire season.

When international firefighting partnerships were first developed under the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre (CIFFC) after it opened in 1982, the “agreements were more informal letters of intent to cooperate and considered for the exchange of information and best practices only,” according to Kim Connors, executive director of CIFFC. “Now,” Kim adds, “all aspects of wildland fire management are included: prevention, mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery.”

Canada currently has formal partnerships with the United States, Mexico, Australia, South Africa, New Zealand, and Costa Rica. “We are at a point where countries need to help each other,” says Kim. Although the relationships are reciprocal—Canada sent a great deal of “resources” to Australia in late 2019 and early 2020 during its infamous “Black Summer” bushfires and to the western United States last September 2021 during its extreme wildfire season—Kim admits that Canada is a “net importer of assistance” from the international agreements.

We are at a point where countries need to help each other.

“Resources” in wildland firefighting jargon is a long list that can include personnel, aircraft, training, and capacity development. Kim emphasizes that at this stage in these global arrangements, when it comes to personnel, all partners “only exchange what we consider the best of the best for this work” and that partner countries are partly identified by their level of training, engagement and the operating system they work under, specifically those who understand the “language” of the Incident Command System, or ICS.

One other factor considered is whether the firefighters from other countries are familiar with working with water: “Canada is rich with water, so we fight fires with water. A lot of countries don’t,” says Kim. If a potential partner country demonstrates gaps in this knowledge, CIFFC weighs how big of a task it would be to train international personnel. South African partners, for example, who supported Alberta in 2015, 2016 (in the Fort McMurray wildfire), and again 2019, required training to learn how to work with pumps and hoses to deliver water to a fire. The reverse is also true; when Canadian firefighters went to Australia, they had to adapt to different methods of fire suppression due to limited access to water.

Canada is rich with water, so we fight fires with water. A lot of countries don’t.

International collaboration is crucial for the province and the entire country also because recruitment itself is an issue in Canada, says Kim. “Normally the provinces, territories and Parks Canada have the capacity for what would be considered a normal or a bit harder-than-normal fire season.” But, he adds, “when you get into these extreme seasons, like now, then agencies will consider their levels of capacity.”

The boys (and girls) of summer

As part of this international wildland firefighting collaboration, a crew of 103 highly skilled—or “Type 1”— Mexican firefighters and supports arrived in British Columbia on July 24, 2021 to help the local crews mitigate and extinguish the hundreds of wildfires that have been active across the province this season. A mobilization of “Operation Yellow Snake,” this particular crew consisted of five brigades composed of 100 field firefighters, two field coordinators, and one COVID-19 supervisor.

Both born in Durango, a northern state in Mexico, brigade leaders Ricardo Pacheco and Juan Ruperto Vergara have 24 years and 13 years of wildland firefighting experience, respectively. This is not the first time that Ricardo and Ruperto have come to Canada; in the past, they have traveled to the country specifically to assist in combating the wildfires. “We have collaborated here in Canada four times,” Ruperto says. “The first year was in 2016 in Alberta, in 2017 in British Columbia, and in 2018, I went to Ontario. This year we have the opportunity to be in British Columbia once again for two 14-day periods.”

Canada is not the only country the Mexican firefighters—“yellow snake” is how the crew refers to itself when supporting an incident or fire outside Mexico—have been deployed to in order to provide their support. In February 2017, Ruperto, along with 57 other firefighters, went to the Araucanía region in Chile to mitigate the aggressive wildfire situation there; Ricardo, together with 99 crew members, helped extinguish the severe wildland fires in the state of California in 2020.

Here in B.C., the relationship between the local and international crews is strong. Despite living in a demanding and stressful environment, they see themselves as one big group in which camaraderie is built all the time. “I would say it is a very good relationship,” says Ricardo. “Being on the line, we are all forest firefighters—we are not Mexicans, we are not Canadians or Australians, we are all the same, and we have learned to be a great, unified team. We have worked very well with the Australians, the Canadians, and our fellow Mexicans.”

Being on the line, we are all forest firefighters—we are not Mexicans, we are not Canadians or Australians, we are all the same, and we have learned to be a great, unified team. We have worked very well with the Australians, the Canadians, and our fellow Mexicans.

Four of the Mexican crew also identify as female, a gender representation which is a slowly changing statistic in firefighting. According to Kim Connors, South Africa leads international wildland community efforts towards gender parity, with approximately onethird of their wildland firefighting program composed of femaleidentifying firefighters. Kim says that when South Africa “exports” their resources, they try to maintain that proportion in their international crews, including those that come to Canada. CIFFC, as an organization, has also begun to undertake purposeful efforts in the area of equity, diversity, and inclusion, adds Kim.

A day in the life

Ricardo and Ruperto briefly talk about the crew’s daily routine: they begin their operational period early in the morning to make the most of daylight hours. They eat breakfast, lunch, and dinner at the same hour every day, but every once in a while there are delicious surprises, like a Mexican banquet with delicious tortillas and other treats—sometimes even with Mexican music. This lifts everyone’s spirits and gives them the boost needed to continue with their tremendous task. On regular days, when the operational period ends around seven in the evening, Ricardo and Ruperto go back to the camp and hold a meeting with all the brigade members and coordinators to debrief their daily activities and the next day’s plans. Once that’s over, they have the freedom to do whatever they like with their time, and take a much-needed rest.

Since Mexican culture is very family-oriented, Ricardo and Ruperto make it a priority to keep in touch with their family throughout their stay. They have an internet connection in their camp, so they mostly talk to their families through social media platforms, text messages, and video calls. However, even though they are in constant communication, it is tough to be apart from their loved ones.

Where the heart is

“I have a five-year-old boy,” says Ricardo. “He wants to talk to me and see me every day. I think he feels the absence the most at this moment because he is so young.” Ruperto shares that his two children are curious and always ask him about his day and about the fires: “They ask me questions all the time.”

It’s clear by their tones that the subject of family is dear to the fathers’ hearts, and being away for so long makes them miss their family even more. “I am going to talk about something very personal,” Ruperto says intensely. “I would like to have the opportunity at some point in life to invite my family to visit the British Columbian landscapes that I have seen while moving from one place to another when we have been in the fires. The landscapes are spectacular; the rivers and lakes that I have had the opportunity to witness are beautiful. I feel the nostalgia of one day being able to share this with my family.”

Being away from family can take its toll on a person, making it very important to create friendships and a support system when out in the field. Ricardo and Ruperto describe their strong relationships with their colleagues, who seem like extraordinary people. Ricardo and Ruperto have also met friendly folks in British Columbia, as well as other parts of Canada, who have been attentive and supportive towards them.

One such person is Gregory Blais—nicknamed “Gregorio” by the Mexican crew—their British Columbia Wildfire Services Liaison Officer. Ruperto reveals that they “have a closeness with him, and [they] have been exchanging many points of view, many conversations.” He adds that they see each other regularly, and it feels like they “have been friends for a long time.”

¿Hablas español?

Building these types of relationships can be complicated by cultural and language differences—but this hasn’t stopped Ricardo and Ruperto (and it helps that “Gregorio” speaks Spanish); they don’t see language as a barrier, more as a tiny hiccough. Ruperto admits that “of course” language was a challenge at the beginning of the journey; however, he says both he and Ricardo have both been learning and improving, and they get excellent support from the translators and the Canadian coordinators. “They too have made the effort to learn our language. They have definitely made our journey better,” Ruperto says.

Mi casa, su casa

The Mexico-Canada arrangement has worked so well for many reasons. One of them, say the two men, is that the fire season differs between the two countries; this situation makes it ideal for the Mexican firefighters to come to Canada without neglecting the needs of their home country. Ricardo explains: “In Mexico, the season has different stages: In the centre and south, it starts in February and ends in June; then, in the north, northeast of the country, it starts at the end of February and ends in July.” Also, the way the fires present themselves is another aspect that works for both countries. Ricardo tells us that some of the ecosystems he has worked in in Mexico are very similar to the British Columbian ecosystem, helping them to successfully fight the fires and adapt to specific environmental conditions here. However, the ecosystems in Ontario and Alberta differ from what they are used to, and sometimes the conditions become more challenging. “Ontario was very surprising,” Ruperto says, “There was a lot of humidity in some parts of the territory, and on the other side, it was on fire. In Mexico, the whole territory is typically dry, but in Ontario we found places with a lot of humidity and other very dry places in close proximity. In Alberta, the fuel we found was very deep and very thin; it took a long time to extinguish it. There was water accumulated on top and below was the fire, which for us was something different.”

Ontario was very surprising. There was a lot of humidity in some parts of the territory, and on the other side, it was on fire. In Mexico, the whole territory is typically dry, but in Ontario we found places with a lot of humidity and other very dry places in close proximity. In Alberta, the fuel we found was very deep and very thin; it took a long time to extinguish it. There was water accumulated on top and below was the fire, which for us was something different.

Not knowing what to expect can be very dangerous; the firefighters have to frequently remind themselves to keep safe, stay focused, and always pay attention to the surroundings because the fire’s behaviour in unfamiliar places can be extreme and unpredictable. Ricardo recalls that sometimes the flames can be ten to fifteen centimeters tall and a moment later be as tall as the trees that surround them.

Firefighters risk their lives to keep people and property safe, and wildland firefighters in particular are being tested to new extremes every day. They are often hailed as heroes who deserve praise and appreciation. The gratitude goes both ways, however, as the opportunity to come to Canada means a great deal to the Mexican crew. They express how meaningful it is to them to have a voice, to be seen, and to contribute their knowledge.

“We are here helping a country, and for that very reason, we must do everything in our power to demonstrate the role we are playing as ambassadors of Mexico,” Ruperto says. “We have this unity with all Canadians. When we are here, they have greeted us in the street; they recognize us, and we are very proud of that. We always try to give the best of ourselves, every single day.”

We are here helping a country, and for that very reason, we must do everything in our power to demonstrate the role we are playing as ambassadors of Mexico. We have this unity with all Canadians. When we are here, they have greeted us in the street; they recognize us, and we are very proud of that. We always try to give the best of ourselves, every single day.

Because of the severity of both Canada’s and the U.S.’s 2021 wildland fire season, the two countries were unable to support each other as they had in previous seasons. To exacerbate things, the pandemic curtailed support to Canada from Australia and New Zealand as well. Kim Connors admits the situation was unfortunate and that the partners are “heartbroken” when they can’t support one another. Kim emphasizes that “constant communication” keeps the relationships strong even when the international partners are unable to deploy support resources in times of need.

The feeling that they are part of something bigger than themselves and also part of a critical, and growing, global network at the frontlines of climate change both motivates and humbles Ruperto and Ricardo: “Yes, we are part of this movement; we know fires [will] become more and more erratic and stronger, and these organizations contribute so that the forces of one country and another can serve at the moment they are needed. So we feel part of it, we are part of it, as are all the participants, from coordinators, fighters, to the many people who are in Mexico who have worked for this—because here they see us. They see 103 Mexicans who are in B.C., but there are many people in Mexico working so that we can show our faces.”

This article was originally published in print in December 2021